THE LAND OF GREEN GINGER

The Land of Green Ginger

Oil on canvas, unravelled remade carpet fractal

270 x 385 cm

2017

Barbara Hepworth said: ‘Perhaps what one wants to say is formed in childhood and the rest of one’s life is spent in trying to say it.’ I agree. What I wanted to say in childhood was that all islands are floating; the world is sometimes confusing but through the chaos there is beauty abundant; blues and greens are the best colours in the world. In many ways this show brings back my island childhood to me and is a fitting subject for my first solo show.

The Land of Green Ginger, along with the 1001 Nights, was a favourite childhood book. I remember the moment I spied it in the library when we’d just moved to England after Hong Kong, which I missed tremendously, and the book’s cover showed a flying island! It was as if the universe had just given me a gift – a sort of link back to my island – and I was thrilled at the coincidence. And when I read it to myself at home I found myself laughing out loud – the perfect antidote to grey skies. Thus I tumbled back into the world of fairytale – the world of the 1001 Nights that I’d just left off in Hong Kong (in fact I was a voracious reader as a child in England; in some ways it saved me from a dreary existence of school and homework and ignited my imagination like nothing else. That’s why I’m such a fan of books, the book arts and libraries – they are transformational).

I still find myself laughing out loud every time I read it – there has to date not been a single instance of me reading it where I have not laughed. I read it annually and it gets me every time. It’s the perfect de-stressor. It’s stereotyped and a product of the era in which it was written (1937 – the original Tale of the Land of Green Ginger was written by Arthur Barker) yet it’s so ludicrous and ridiculous that it is genuinely funny. Not only is it funny, it’s heartwarming with lovable characters and an exciting plot (what happened after Aladdin had kids?) too. I own almost all editions of this wonderful book and look forward to sharing it with my own family.

My piece is entitled The Land of Green Ginger in homage to this favourite childhood title of mine. A flying, errant island that bumbles along wherever its fancy takes it, despite attempts to control it. When the Magician does manage to steer it properly, he has to go through a lengthy magical process first and although the island is his own creation, it still has a mind of its own. In my painting, lava seeps down slowly, anointing the giant stone which is the signal for it to break free from its womb-like cave, dripping in the blues and greens of island colours. Many a new island is formed by the volcanic process, giving birth to baby islands in the sea. The big rocky island in my painting has detached from its slippery cave and is about to take off and fly, supported by a cloud-like Chinese carpet cut, unravelled and re-fringed in the shape of a fractal. It comes into sharper focus as it unpeels itself from the background and prepares for its own flight. The carpet rests on the floor, as it’s still earth-bound, but is also attached to the painting, in the process of becoming buoyant. It’s resting potential – a subject I will explore in other works (in the tapestry roots pieces the lift-off has already occurred; flight has already happened and the pieces are up on the walls). There is a passage in The Tale of the Land of Green Ginger where the magic flying carpet tries to lift Abu Ali and Princess Budur to safety but alas, cannot fit through the window, so simply hangs there, motionless. Carpets and rugs are supposed to be on the floor, but sometimes they are meant to fly – this one is in the middle of both.

The feeling of lift-off and weightlessness is one I always loved as a child when planes were taking off. I likened waiting to give birth to this feeling (see my earlier post here) – birth in itself is a process of shedding weight in order to become ‘higher’ – spiritually higher also. My yoga teacher mentioned that yogis spend years trying to attain enlightenment and one quick way to glimpse it is simply to give birth! This glimpsing of enlightenment is also pictured in what I call my ‘Pockets of the Universe’ parts of paintings. We live a mundane existence but occasionally – just occasionally – we are given glimpses of greatness, seeing, out of the corner of one’s eyes, slits where the infinite pours in, flashes of the universe where we suddenly see in sharp focus how everything is connected and how we are connected to it. It’s almost like looking down on oneself from high above, floating in space. It’s where inspiration lies and this semi-weightless feeling is encapsulated in this work.

My carpet is remade into a fractal shape. Fractals are themselves forms found in clouds and coastlines and were a teenage interest of mine; I grew up when fractal art, digital arts and Photoshop were just beginning to get good, and I remember getting the latest digital arts magazines and poring over the millions of fantastic digital colours then painstakingly trying to replicate them in oils. It’s not always possible; projected light is different to reflected light, and RGB colours on screen differ from CMYK print colours, or paint colours. The struggle between the two still fascinates me. In some ways my own unique colour sense has been shaped by my early island memories in Hong Kong, my teenage fascination with fractals and computer arts and my longstanding interest in miniature painting. My carpet was obtained after long and steady persistence – it originally belonged to my husband but since the shapes and colours in the carpet were just perfect – the blues and greens echoed perfectly the ones in my paintings, and although I’d obviously had other carpet opportunities it simply HAD to be this one since I saw it almost every day and it became ingrained into my consciousness – after around 7 years of consistent gentle pressure (he would argue otherwise) he eventually caved in and I was able to complete this work (!). It was an old, tired and worn carpet and I wanted to give it new life by lovingly cleaning it, reshaping it and remaking it into art. Luckily he likes it!

A fractal is an infinite shape and cannot really be contained. Similarly, the patterns in carpets and the Islamic book arts (tazhib illumination) are inexhaustible in their variety and so buzzing and bursting with energy that it makes sense to me to allow them freedom (seen also in my Floating Neshan, which is so free that it floats high above the gallery space!). I have always enjoyed playing with the frames and doodling in the margins. I don’t believe that my work should be confined within the edges of the canvas, or frame, or box. Mughal and Persian artists understood this: the rocks, which I studied on my MA, regularly burst free from their margins. Medieval scribes also enjoyed doodling in the margins of their manuscripts and schoolchildren do this intuitively too. I enjoy having the boundaries of the box – if only to escape them later. Know the rules well, said the Dalai Lama, in order to break them effectively.

The dialogue between the painted image and the burst margin is one that interests me tremendously because it’s where you see the true location of the art, the true meaning, the truth! Truth is hidden between the lines, in between the main image and the commentary on the side. And I’m always seeking similarities, not looking for differences, so that sympathetic materials can have conversations. Creative associations and unlikely alliances can be formed.

Having a margin to play with allows for these new realities to be made. It’s not just one image anymore, nor is it simply two adjacent images – it’s two images with a kind of emergent ‘third space’ – the space in between them – where a new meaning lies. The juxtaposition of two complex images creates a boundary or border where they meet. The visual leap between the main image and the image of the margin/frame is like a footnote, an asterisked comment, a ‘by-the-way, did-you-know…?’ that changes one’s entire reading of the piece. This is exciting and this is where the ‘art’ lies. It encourages active, not passive thought processes and the visual leaps inspire mental leaps. Think outside the box. Be creative in thinking. Make unusual connections. Everything is connected. The thing inside the box and the thing outside are always connected. Mine are sometimes connected by colour, or a similar shape or form, or otherwise tenuous connections that suddenly make sense after deep thought or contemplation. In a roundabout way, it’s like being mixed-race (or ‘mixed-race other’ like me!) and having a natural duality in which to spring back and forth. The most interesting things happen at the side, or on the edges, where two (or more) things meet.

So it is with The Land of Green Ginger: for me it is the beginning of something, the resting potential, gathering its energies before it takes off into full flight ~

*Here are some excerpts from the book:

‘Fortune preserve you, gentle reader. May your days be filled with constant joy, and may my story please you, for it has no other purpose.

‘And now, if we are all ready to begin, I bring you a tale of the wonderful wandering of an enchanted land which was never in the same place twice.’

‘Everyone present rose and bowed as he departed for the balcony, and the Lord Chamberlain rather forlornly wrote ‘Bang’ on his piece of paper, and then thought better of it and drew little faces down the side instead, to help him concentrate.’ (Just as I do – doodling is great!)

“The Land of Green Ginger,’ announced the Djinn impressively, ‘was built by a Magician who was very fond of fresh vegetables. The idea was that when he went travelling, he could take the Land of Green Ginger with him like a portable kitchen-garden, only fancier’

“It’s always where you’d LEAST expect it to be. For example, a tired travelled might go to sleep on a barren desert, and wake up with his feet up a tree and his head on a mushroom.’

“You know, your mother always WAS a little too verbal,’ he said thoughtfully. ‘Wouldn’t she be more valuable to collectors if she were to stay like that?’ (Thus the Djinn Abdul freezes Aladdin’s mother into a porcelain figurine!)

“By the way,’ he added insincerely, ‘I’ve forgotten the spell that restores decorative ornaments to humdrum life. Does anybody mind?’

‘The Shah of Persia sent a politely worded invitation to his son, the vapid, vindictive Prince Tintac Ping Foo; requesting the dubious honour of his presence on a matter of urgent importance; and after Prince Tintac Ping Foo had deliberately kept the Shah of Persia waiting for forty-two minutes, he haughtily presented himself.

“Ah, Tintac Ping Foo,’ said the Shah of Persia ingratiatingly, ‘I want to have a friendly, man-to-man, equal-to-equal, father-to-son talk with you, my boy.’

“Oh, you do, do you?’ riposted Tintac Ping Foo ungraciously. ‘Well, if it’s about cheating at chess, I wouldn’t bother, because I ADORE cheating at chess; I shall continue to cheat at chess; and if you DARE to stop me, I shall put glue in your beard!’

(On his rival, Prince Rubdub Ben Thud of Arabia)

“That balloon-faced butterball? Do you DARE to tell me he has the silly sauce to pit himself against a paragon of lovable manly virtues like me?’

‘Ho there, Slaves! My camels! My retinue! My magic sword! My jellybeans! I leave at once for Samarkand!’

‘The donkey, laughing quietly to himself, sat down as before; but having reckoned without the tack, he sat down on that.

‘Like a homing swallow, like a comet in the sky – like a donkey that had just sat down on a tack – he sped down the street, and Abu Ali and Omar Khayyam held on like fury.’

‘His name was Kublai Snoo, and he could wiggle his ears.’

‘There in the clearing, dancing about and not noticing them as yet, was a huge, horned, scaly, scowly, nozzle-nosed, claw-hammered, gaggle-toothed, people-hating, smoke-snorting, fire-eating, flame-throwing, penulticarnivorous, bright green Dragon.’

‘Then the green smoke slowly faded to reveal a small, round, fat, fourteen-carat, rueful, green-hued Djinn seated on the grass, looking more than slightly dazed.’

“Would you care to repeat that without a potato in your mouth?’ asked Ping Foo superciliously.’

“LOOK!’ said Sulkpot in an alarmingly hoarse whisper. ‘The next sound EITHER of you makes, you’ll BOTH go straight into the boiling oil! Is that absolutely clear?’

‘Yes,’ said the Captain of the Guard.

‘No,’ said Kublai Snoo.

‘WHAT?’ roared Nagnag, clutching at the couch.

‘He can’t throw us in the oil vat,’ said Kublai Snoo to the Captain serenly. ‘It’s our afternoon off in a minute. We caught a suitor!’

‘Kublai Snoo and the Captain beamed and marched one pace forward smartly, expecting promotion or at least a medal.

‘Sulkpot stretched out both his arms and banged their helmets together.’

There are many more but I can’t include the whole book here. This tale has many plays on language and a tight, witty, clever use of English so I look forward to sharing it with my family. Every sentence is perfectly crafted. It’s also great for reading out loud.

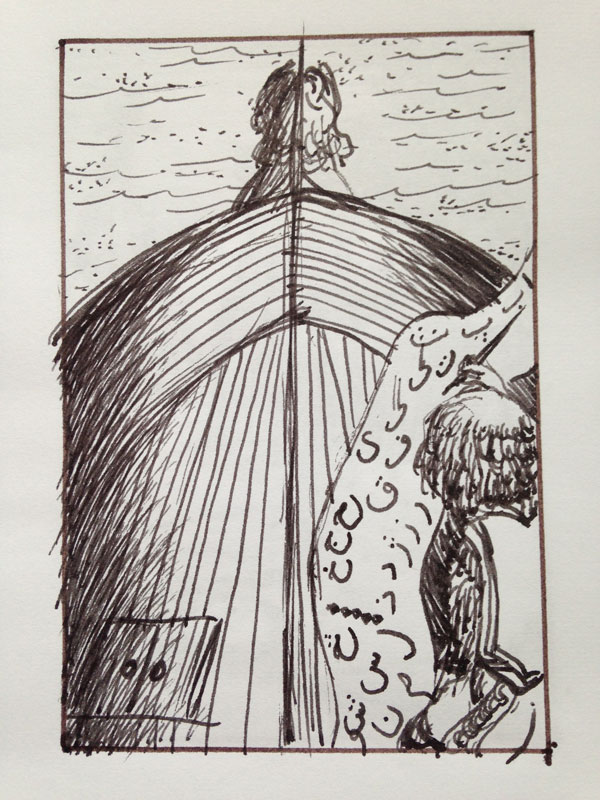

Here are some of the Edward Ardizzone illustrations: